Andrej Karpathy broke engineering Twitter in February when he tweeted about "vibe coding"—just "fully give in to the vibes, embrace exponentials, and forget that the code even exists." Half my timeline lost their minds calling it irresponsible. The other half started posting screenshots of entire apps built without touching a keyboard.

Both sides are missing the point.

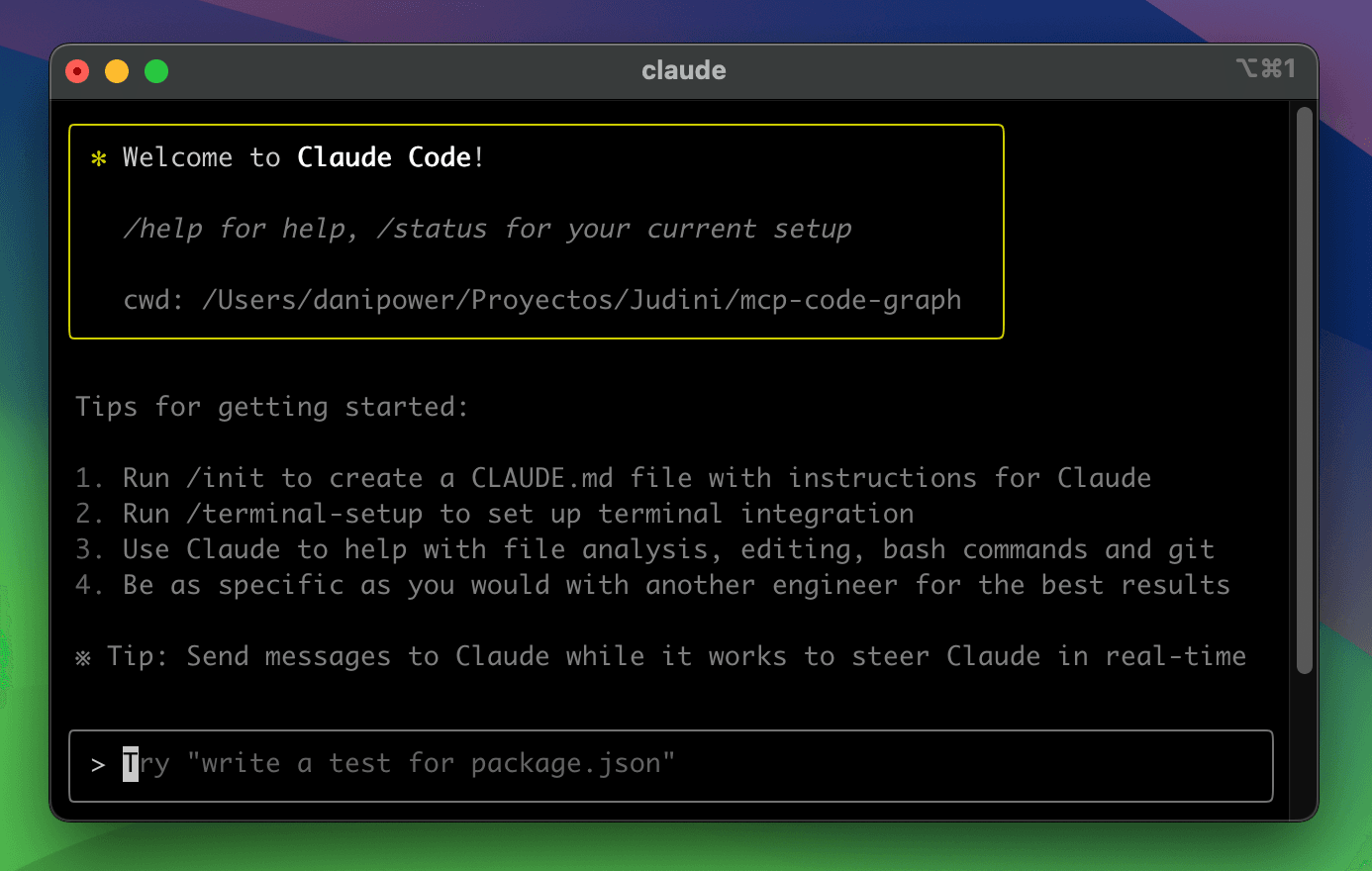

I know because I tried the "forget code exists" thing. In January 2025—one month before Karpathy coined the term—I took myself on a challenge. I was going to stop writing code. Entirely. For two months, I'd write only prompts. No touching the IDE. No fixing the AI's semicolons. Just pure, unadulterated delegation.

It felt ridiculous. I had a real feature to ship—study group functionality for one of my projects—and I was sitting there typing English instructions into a terminal while Claude did the typing. The first few days, I kept reaching for the keyboard. Muscle memory is a hell of a drug. But after three days of forcing myself to only describe what I wanted, something weird happened.

I realized I had no idea what I was actually doing.

Not technically—I knew how to build the feature. I'd been coding since I turned 18, spent six years in the trenches, shipped production systems, debugged race conditions at 3 AM. I was a good engineer. But I was also burned out at 24, staring at the same patterns, the same syntax, the same Jira tickets. The challenge wasn't about productivity. It was about survival.

So there I was, supposedly "vibe coding," watching Claude generate a database schema for study groups. And it was wrong. Not wrong-wrong—it would work. But it was naive. Missing indexes. No consideration for how we'd query it in the UI. No thought about data retention. I caught myself thinking, "Jesus, I'd have to rewrite this whole thing."

Then I caught myself catching myself.

I had felt this exact frustration before. Last year, working with a junior dev on a caching layer. He'd submitted a PR that "worked" but missed every operational concern—monitoring, eviction policies, cache warming. I'd been annoyed. Tempted to just write it myself. But I didn't. I sat down, explained the requirements, the context, the edge cases. Asked him to try again. The second attempt was solid. The third, elegant.

That's when it clicked. I wasn't vibe coding. I was managing a junior developer who happened to be made of weights and biases. And I was micromanaging poorly.

The Team Lead Epiphany

Here's the thing nobody tells you about vibe coding: it's not a coding skill. It's a management skill. And most engineers are terrible managers.

We've spent our careers optimizing for individual execution. Type faster, know more patterns, keep more context in working memory. The best engineers are autonomy machines—you hand them a problem, they disappear for three days, they return with elegant code. That model breaks the moment you introduce AI.

Because you can't just "disappear and code" when you're not the one coding. You have to stay. You have to explain. You have to wait while the AI asks clarifying questions or—more often—doesn't ask them and builds something subtly broken that you'll catch three days later when the integration tests fail.

I saw this clearly during the study group project. I asked Claude to build the matching algorithm—pairing students with similar study habits. It generated a neat little Python function with collaborative filtering, looked good on the surface. But I hadn't specified the latency requirements. Or the privacy constraints. Or the fallback behavior when we didn't have enough data on a new student. Classic junior dev behavior: solve the happy path, ignore the operational reality.

In my old life, I would have just rewritten it. Taken me twenty minutes. But my challenge forbade that. So I did what I'd do with a human junior: I wrote a review. Detailed. Specific. "This doesn't handle cold-start users. We need O(n) complexity max because this runs on page load. We can't store raw behavioral data due to privacy regs—use differential privacy or k-anonymity."

Claude revised it. Better. Not perfect—I had to do three more review cycles—but by round four, it was production-grade. And something in my brain had rewired.

I wasn't vibe coding. I was conducting an orchestra. I was a tech lead.

The definition matters here. When Karpathy said "forget the code exists," he meant something playful—exploring ideas without friction. But that's not what production engineering is. Production engineering is risk management. It's knowing that code is liability, that every line is a potential bug, that "works on my machine" is the enemy.

So I'm proposing a different definition. Vibe coding isn't about ignoring the code. It's about trusting the process of delegation—the same process that lets a senior engineer scale their impact by leading a team of five juniors instead of writing solo. The "vibe" isn't carelessness; it's the flow state of high-bandwidth communication between a technical lead and capable implementers.

The constraint forces growth. With a human junior, you can't say "wait, I'll write it myself" because that's demoralizing and unsustainable. You have to improve your communication. You have to get better at context-setting, at anticipating failure modes, at writing specifications that don't assume shared intuition. AI removes the interpersonal guilt, but the skill requirement remains identical.

And here's the uncomfortable truth: that's why people hate it.

It's not that AI writes bad code. It's that effective vibe coding exposes how much of our "senior" work was actually just pattern-matching and syntax memorization—things AI is great at. The remaining work—architecture, specification, verification, risk assessment—is harder. It's less tangible. It feels slower because you can't measure it in lines of code shipped.

But it's the only part that actually matters at scale.

The Workflow (Why Vibe Coding Takes Longer, Not Less Time)

So if communication is the new bottleneck, what does the actual process look like? Not the "write a prompt, get code, ship it" fantasy—the reality of responsible AI-assisted development.

I kept a log during my study group project. A feature that would have taken me two days of heads-down coding took five days of "vibe coding." But the resulting code had fewer bugs in production than my solo work from six months prior. Here's where the time actually went:

Brief → Spec. Instead of opening my IDE, I opened a text editor. I wrote a brief—user stories, acceptance criteria, the scope boundaries. Then I prompted Claude: "Convert this brief into a technical specification. Ask me questions until you have enough context." We went back and forth for forty minutes. It felt slow. Tedious. Exactly like onboarding a new hire.

Spec → Test-case. "Given this spec, what are the critical test cases?" Claude proposed tests. I rejected half—too superficial, missed edge cases. We iterated. By the end, I had a test matrix I wouldn't have thought of alone, partly because thinking about testing your own code is cognitively hard, but reviewing someone else's test proposals is easy.

Test-case running. This is where the first code appeared—not implementation, but test scaffolding. Running them confirmed they failed appropriately (red tests). This took an hour. In my old workflow, I'd have skipped straight to green.

Test-case → Automation. "Automate these tests into CI/CD. Include linting and type checking." More back-and-forth on configuration. Boring. Necessary.

Spec → Plan. "Design the architecture. Consider the existing codebase [context provided]." Claude proposed a structure. I had to correct it—"We don't use that pattern here, we use ports-and-adapters"—which required explaining our architectural philosophy. Teaching moment.

Plan review. Here's where I used multi-modality. I took Claude's plan and fed it to GPT-4 and Gemini. "Critique this architecture. Find the failure modes." They disagreed on database choice. One flagged a race condition the others missed. I synthesized. This is peer review, just without the calendar scheduling.

Plan → Estimate. "Estimate complexity. Flag risks." The AI identified a third-party API integration as high-risk. I agreed. We built a mock interface first—something I might have YOLO'd in my solo days.

Plan → Code. Finally. But even here, the constraint forced discipline. I couldn't just "fix it" when I saw a variable name I didn't like. I had to describe the change. "Rename

datastudentPreferencesPR → Review. The code came in chunks. I reviewed like I would a junior's PR—line by line, questioning assumptions. Caught a potential N+1 query Claude hadn't considered. Sent it back.

Review → Fixes. Iteration. Slow. Frustrating.

PR → Updated docs. "Update the technical documentation and API specs." Auto-generated, but I had to verify accuracy.

The Columbia Computer Science study hit my inbox midway through this project. They found that most serious problems in AI-generated code are error handling and business logic—precisely the things you catch when you don't skip steps. The MIT study dropped shortly after: experienced developers were 19% slower with AI assistants on non-trivial tasks. The bottleneck? Review and verification. The cognitive load of checking someone else's work.

I wasn't an outlier. I was the data point.

What felt like "vibe coding" was actually the full software engineering lifecycle, uncompressed. When I code alone, I compress steps. I hold the spec in my head, skip formal test-case definition, merge architecture and implementation, assume I know the edge cases. Sometimes I'm right. Often I'm not, and I pay for it in production bugs.

With AI, you can't compress. The context window is too small for implicit understanding. The AI will happily code based on assumptions you didn't know you had. So you're forced to externalize every step. Slow? Yes. Thorough? Yes. This isn't vibe coding as carefree generation. This is vibe coding as rigorous engineering process management.

And here's the crucial part: every step is a skill. Prompting for specs is different from prompting for tests is different from prompting for architecture critique. I wasn't learning one "AI coding" skill. I was learning eleven distinct context-provision skills. I was becoming a technical program manager who happened to output natural language instead of Jira tickets.

The study group feature shipped. It worked. But more importantly, I had a map for how to do this again. Not faster—better.

The Three Techniques

Three techniques emerged from that project that I now use religiously. They're not coding techniques—they're management protocols adapted for silicon-based reports.

Multi-modality, or The Ensemble Method

I mentioned running Claude's architecture plan by GPT-4 and Gemini. That wasn't a one-off. That became my default for any decision with consequence.

Here's the insight: individual LLMs have cognitive biases, same as humans. Claude tends toward over-engineering—beautiful abstractions that solve problems I don't have. GPT-4 is reckless with dependencies—"just pip install this obscure package" without checking if it's maintained. Gemini is cautious to the point of paralysis—"consider security implications" without ever committing to an implementation.

Sound familiar? It's your team dynamics. You have the over-engineer, the cowboy, and the analysis-paralysis junior. A good tech lead doesn't pick one and hope. They assign the same task to multiple people, compare the approaches, and synthesize.

I formalized it. For any component with >low complexity, I run a three-way. "Build the study group matching algorithm." Claude gives me the collaborative filter with bells and whistles. GPT-4 gives me a brute-force SQL approach that'll work but won't scale. Gemini gives me a 500-word essay on privacy regulations.

Then I cherry-pick. I'll take Claude's algorithm structure, GPT-4's database pragmatism, and Gemini's privacy checklist. The synthesis takes ten minutes of comparison. The result is better than any single output—and honestly, better than what I'd have written solo in my tired 4 PM state.

The research backs this up. Studies on multi-agent workflows show 2.3x speedups not because individual agents are faster, but because you avoid the "rewrite from scratch" moments when your first approach hits a wall you didn't anticipate. It's parallel thinking.

The overhead is real—you're running 3x the API calls, managing 3x the context windows—but it's still faster than the alternative, which is debugging production at 2 AM because your "vibe" missed a race condition.

Context Engineering, or Teaching the Domain

The biggest mistake I see in AI-assisted development is under-contextualization. People treat LLMs like they treat Google—query, answer, done. But they're not search engines. They're junior developers who just transferred from a different company and don't know your stack, your business logic, or that time you tried microservices and it went poorly.

You have to onboard them.

I started cloning repositories. Not just the one I was working on, but dependencies. If I'm building a feature that touches our auth system and our notification service, I'd clone both into the context window. "Here is our current auth implementation. Here is how we handle permissions. Study them before proposing changes."

I fed it meeting recordings. I'd record a 20-minute Loom explaining the business logic of study groups—how students actually behave, what "engagement" means to the product team, why we care more about retention than raw matches. Transcribe it, feed it to Claude. Now the AI has the tribal knowledge that isn't in any README.

This is the shift from "vibe coding" to "context engineering"—a term I started seeing in industry reports midway through 2025. The skill isn't prompting; it's information architecture. Knowing what context matters, how to structure it, when to inject it.

The difference is night and day. A prompt like "build a study group matcher" gets you a toy. A prompt like "Build a study group matcher. CONTEXT: [paste of current user schema] [transcript of product meeting] [relevant open-source implementations from GitHub]. CONSTRAINTS: Must handle cold-start users. Must respect privacy policy [paste]. Must integrate with existing notification service [paste repo]"—that gets you production code.

It takes 30 minutes to prepare that context. It saves you three days of iterations.

Chain of Verification, or The Review Culture

The final technique is cultural, not technical. You cannot trust first outputs. Ever.

I developed a ritual. Every time Claude generated code, I'd run a verification pass. "What assumptions did you make that I didn't specify?" "What would cause this to fail silently?" "How would you test the edge cases?"

If the AI answered immediately with confidence, my prompt was bad. Good prompting should force the AI to ask you questions. "What is the maximum latency?" "Do we need to handle offline mode?" These questions are signals that the AI is engaging with the spec seriously, not just pattern-matching to Stack Overflow.

It's the Socratic method applied to synthetic reasoning. And it mirrors exactly how you review junior code. You don't just say "fix this." You ask "what happens if this list is empty?" and watch them realize they forgot a null check. The goal isn't to catch the bug—it's to train the developer to catch it themselves next time.

With AI, the training is for you. Every time you have to specify "handle the empty list case," you learn to include that in your next prompt. You're not just building software. You're building a specification style. You're becoming the architect who never leaves fingerprints on the code but whose mind is everywhere in it.

Why Your AI Writes Bad Code (And It's Your Fault)

I can hear the objections already. "This sounds like a lot of work to get code that still needs debugging." "AI generates spaghetti code." "It's faster to write it myself than fix its mistakes."

You're right. And you're proving my point.

The Columbia study I mentioned earlier analyzed hundreds of AI-generated code submissions. The most common serious problems weren't syntax errors—those get caught immediately. They were error handling failures, business logic gaps, and silent assumptions. In other words, the AI wrote code that worked for the happy path but failed catastrophically at the edges.

Sound familiar? That's exactly what happens when you give a junior developer a 30-second verbal brief and they go heads-down for two days. They didn't write bad code because they're incompetent. They wrote bad code because you didn't specify the failure modes, the edge cases, the operational constraints.

When people say "vibe coding produces bad code," what they mean is "I prompted poorly and didn't review thoroughly." They're describing the blind-trust version of AI interaction—the "forget code exists" fantasy that Karpathy was evangelizing. That's not what we're doing here. We're doing managed AI development, and managed AI development produces code quality directly correlated to the quality of your specification.

I learned this the hard way during week three of my challenge. I asked Claude to implement the "invite to study group" feature. Simple, right? Just an endpoint, a database entry, a notification. Claude generated it in thirty seconds. Clean code. Worked on first run.

It also had no rate limiting, no abuse prevention, no verification that the invitee actually knew the inviter. I didn't specify those requirements because they were "obvious." In my head, obviously you wouldn't let someone spam invites to strangers. But Claude isn't in my head. It's a junior dev on their first day who doesn't know your company culture, your abuse patterns, your user demographics.

I had to go back and remediate. Not by rewriting the code—by my challenge rules, I still couldn't touch the IDE—but by writing a detailed security review. "Add rate limiting per user per hour. Add relationship verification. Add invite expiration."

Claude fixed it. Took ten minutes. The resulting code was more robust than my usual solo work because I'd been forced to externalize my implicit threat model.

The "bad code" critique is actually a critique of lazy management. It's the equivalent of dumping a Jira ticket on a new hire with the title "Build auth" and no acceptance criteria, then complaining when they build username/password without 2FA. You get exactly what you specify. The AI doesn't hallucinate bad practices—it optimizes for the shortest path to your described goal. If your description is incomplete, the shortest path cuts corners.

This is why senior engineers—ironically—struggle most with AI adoption. They've spent a decade optimizing for implicit understanding. They know "build a cache" means "with eviction policies, warming strategies, monitoring, and graceful degradation" because they've been burned before. So when they prompt "build a cache" and get a basic dictionary, they think the AI is stupid.

The AI isn't stupid. The engineer is just a bad manager. They've forgotten what it's like to work with someone who hasn't internalized the scars of production outages.

Research from Index.dev backed this up. Senior developers with AI assistants were 19% slower on complex tasks—not because the AI was slow, but because the cognitive load of specification and review outweighed the coding speed gains. They were spending their time doing the things they used to skip in their heads.

That's not a bug in the process. That's the process working as intended.

The fix isn't to avoid AI. It's to accept that you're not a solo contributor anymore. You're managing a team of enthusiastic, naive, literal-minded junior developers who happen to execute in Python rather than neurons. Your job is context, constraints, and verification. The coding is theirs. The architecture is yours.

If the code is bad, look in the mirror. Your brief was bad. Your review was rushed. Your context was thin.

Fix your management, fix your code.

The Career Shift (From IC to Tech Lead)

I want to talk about the fear. The one that keeps senior engineers up at night. The "am I going to be replaced?" fear.

You've seen the headlines. GitHub Copilot writes 40% of code in some orgs. Devin builds entire features autonomously. The vibe coding memes show non-coders shipping products. And you—you with your decade of React patterns, your hard-won debugging intuition, your scar tissue from outages—are supposed to compete with that?

You're asking the wrong question.

The threat isn't AI replacing engineers. The threat is engineers who refuse to become managers. Not people managers—nobody's forcing you to do one-on-ones and performance reviews—but technical managers. Architects. Specification authors. Reviewers.

For twenty years, "senior engineer" meant "writes code faster and better than juniors." That definition is dying. The new definition is "produces correct systems through others."

This isn't a demotion. It's a promotion you didn't know you were ready for.

Remember my burnout? At 24, six years in, I was DONE. Not with technology. With typing. With the regex puzzles. With the "refactor this component because the design team changed a margin" treadmill. I had become a highly paid code typist with a good memory for syntax.

Vibe coding—proper vibe coding, the management-heavy version—saved my career. Because it forced me up the stack. I wasn't memorizing pandas DataFrame methods anymore. I was designing data pipelines and teaching them to Claude. I wasn't debugging indentation errors. I was debugging intent—why did the AI think this field was optional when it's actually required? What context did I fail to provide?

The work became abstract. Harder in some ways—you can't google "how to specify a distributed system correctly" as easily as "how to fix pandas SettingWithCopyWarning." But infinitely more engaging. I was mentoring, not executing. And mentoring scales.

I see this as the career path now. Junior engineers type code. They need to, to learn the feel of it. Mid-level engineers use AI as autocomplete—faster typing, still execution-focused. Senior engineers use AI as a team—specification, review, architecture. Staff engineers manage fleets of AI agents across system boundaries.

If you're clinging to the keyboard because you think typing is your value, you're already obsolete. The value was never the typing. It was the judgment. The "what should we build and why." The "what happens when this breaks at 3 AM." The "how do we change this six months from now without breaking everything."

AI is terrible at all of those. You just forgot to charge for them because you were bundling them for free with your syntax skills.

My study group feature shipped. It worked. But more importantly, I worked—sustainably, enthusiastically, for the first time in years. I wasn't burned out because I wasn't doing the parts that burn people out: the mechanical translation of thought into syntax character by character. I was doing the part that energizes: the thinking.

The irony is delicious. To stay an individual contributor, you have to learn to delegate. To avoid being replaced by AI, you have to become the thing AI can't be: a technical leader with taste, judgment, and the patience to teach.

Try it. One feature. One real thing you need to ship.

Write exactly zero lines of code. Don't touch the IDE. Spend your time in a text editor, writing specifications, asking questions, reviewing outputs, providing context. Run the multi-way. Do the verification chains. Embrace the slowdown.

It will feel wrong. It will feel lazy, like you're not "really" working. You'll want to just fix it yourself. Resist.

Notice what actually takes your time. It's not the prompting. It's the thinking. The clarifying. The anticipating of failure. The weighing of tradeoffs. That's not vibe coding as recreation. That's engineering as management.

Stop asking "Will AI replace developers?" Start asking "Am I ready to manage a team of enthusiastic, inexperienced junior developers who happen to be made of silicon?" Because that's the job now. That's the only job that scales.

The code still exists. Every line still matters. You just have to remember: you're not the one writing it anymore.

You're the one ensuring it's worth writing.